New Horizons

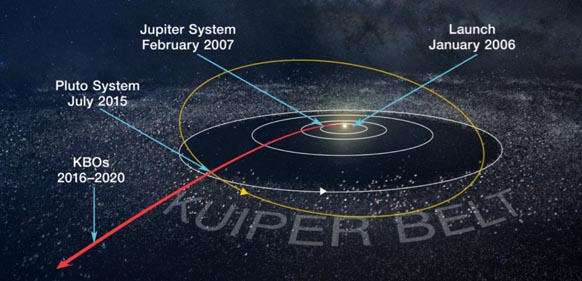

New Horizons is a NASA mission to study the dwarf planet Pluto, its moons, and other objects in the Kuiper Belt, a region of the solar system that extends from about 30 AU, near the orbit of Neptune, to about 50 AU from the Sun.

New Horizons was launched on June 19, 2006, and after a long journey of 9 years, in July 2015, it reached its primary goal: Pluto and its moons.

During the trip, in February 2007, flew-by Jupiter to use it as a catapult in a gravity assist maneuver to increase his speed to reach Pluto. Meanwhile, New Horizons obtained new information that allowed to understand a little bit more the features and dynamics of the Jupiter’s moons.

Long before reaching Pluto, New Horizons discovered two small new moons of Pluto: Kerberos and Styx, in 2011 and 2012 respectively.

Finally, at July 14, 2015, New Horizons flew about 7,800 kilometers above the surface of Pluto. About 13 hours later, a 15-minute series of status messages was received at mission operations at Johns Hopkins University’s APL (via NASA’s Deep Space Network) confirming that the flyby had been fully successful.

Besides collecting data on Pluto and Charon (the Charon flyby was at about 28,800 kilometers), New Horizons also observed Pluto’s other satellites, Nix, Hydra, Kerberos and Styx.

The download of the entire set of data collected during the encounter with Pluto and Charon, about 6.25 gigabytes, took over 15 months. Such a lengthy period was necessary because the spacecraft was roughly 4.5 light-hours from Earth and it could only transmit 1-2 kilobits per second.

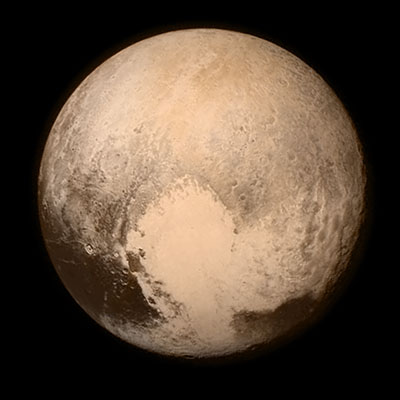

Data from New Horizons clearly indicated that Pluto and its satellites were far more complex than imagined, and scientists were particularly surprised by the degree of current activity on Pluto’s surface. The atmospheric haze and lower than predicted atmospheric escape rate forced scientists to fundamentally revise earlier models of the system.

Pluto, in fact, displays evidence of vast changes in atmospheric pressure and possibly had running or standing liquid volatiles on its surface in the past. There are hints that Pluto could have an internal water-ice ocean today.

Pluto photographed by New Horizons in July 2015. NASA / Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory / Southwest Research Institute

On Charon, images showed an enormous equatorial extension tectonic belt, suggesting a long-past water-ice ocean.

NASA's New Horizons spacecraft captured this high-resolution enhanced color view of Charon just prior to closest approach on July 14, 2015. NASA / JHUAPL / SwRI

Thanks to this mission, it was finally possible to determine the real size of Pluto, which turned out to be somewhat larger than previously estimated, it is 2,370 km in diameter. In addition, the diameter of the moon Charon could be confirmed at 1,208 km.

In the fall of 2015, after its Pluto encounter, mission planners began to redirect New Horizons for a Jan. 1, 2019, flyby of Ultima Thule (officially named 2014 MU69), a Kuiper Belt Object that is approximately 4 billion miles (6.4 billion kilometers) from Earth.

The goal of the encounter was to study the surface geology of the object, measure surface temperature, map the surface, search for signs of activity, measure its mass, and detect any satellites or rings.

On Jan. 1, 2019, New Horizons flew past Ultima Thule, the most distant target in history.

Initial images hinted at a reddish, snowman-like shape, but further analysis of images taken near closest approach—New Horizons came to within just 2,200 miles (3,500 kilometers)—revealed just how unusual the KBO’s shape really is.

At about 22 miles (35 kilometers) long, Ultima Thule consists of a large, flat lobe (nicknamed “Ultima”) connected to a smaller, rounder lobe (nicknamed “Thule”). The strange shape was the biggest surprise of the flyby. No rings or moons were spotted.

Ultima Thule's striking double potato shape photographed by New Horizons on its approach flight in January 2019. NASA / JHU-APL / SwRI // Roman Tkachenko

As of March 2019, New Horizons was about 4.1 billion miles (6.6 billion kilometers) from Earth, operating normally and speeding deeper into the Kuiper Belt at nearly 33,000 miles (53,000 kilometers) per hour.

The New Horizons mission is currently extended through 2021 to explore additional Kuiper Belt objects.

Having visited Pluto and the small 2014 Kuiper Belt object MU69, NASA's New Horizons spacecraft is heading out of the solar system. NASA / JHUAPL / SwRI

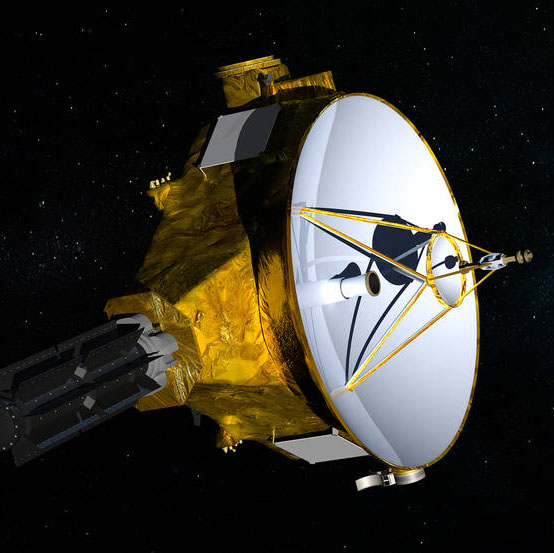

First spacecraft to explore Pluto and its Moons up close

2. Alice-Ultraviolet Imaging Spectrometer

3. Radio-Science Experiment (REX)

4. Long-Range Reconnaissance Imager (LORRI)

5. Solar Wind and Plasma Spectrometer (SWAP)

6. Pluto Energetic Particle Spectrometer Science Investigation (PEPSSI)

7. Student Dust Counter (SDC)

Information: NASA